The Future of Multifocal Contact Lenses (Inspired by the Past)

If you are over the age of 45, you have probably had two quiet reckonings recently. First, you notice your phone has been drifting progressively farther away from your face. Second, you find yourself poking around the settings on your iPhone trying to find the font size menu.

Welcome to presbyopia. The crystalline lens inside your eye has been slowly losing its ability to flex for awhile now, making the shift from far to near focus increasingly inefficient. Around the age of 45, those accumulated effects finally cross the threshold from theoretical to noticeable.

For decades, the solution was simple: strap some magnifying lenses to your face aka reading glasses. They work. They are inelegant. They are also perpetually going missing. Multifocal contact lenses promise an escape from that routine, but they introduce a far more difficult optical problem than most marketing campaigns are willing to admit.

The Problem of Simultaneous Vision

Progressive glasses work because you direct your gaze through one power at a time. Distance up top. Near at the bottom. Intermediate in the middle. The visual system receives a clean signal.

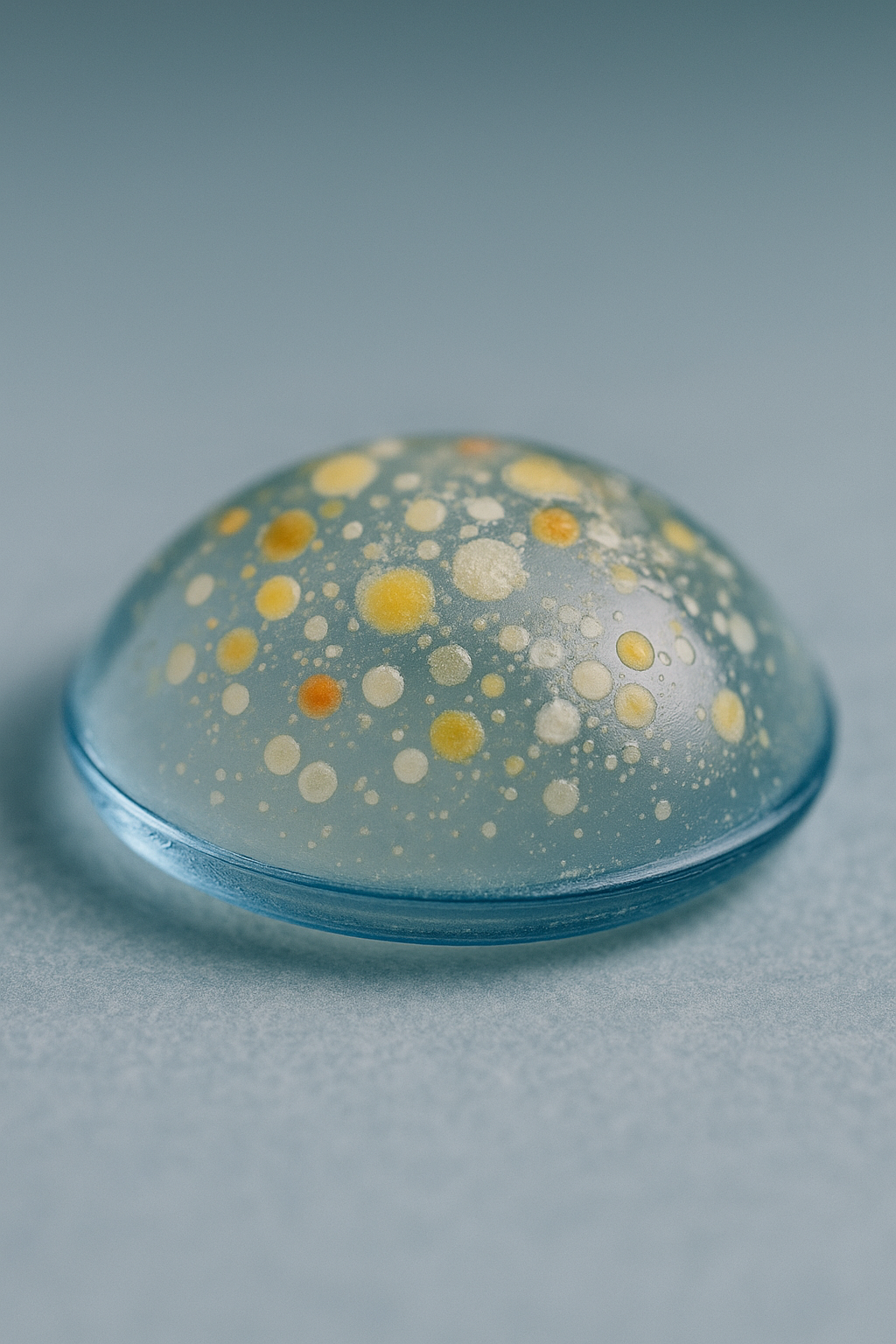

A contact lens does not have that luxury. Because the lens moves with the eye, there is no looking above or below a zone. Instead, most multifocal contact lenses are built as concentric power rings. Think of a bullseye. Each ring carries a different prescription, distance, intermediate, or near, and all of them sit directly over the iris.

As a result, all focal zones are optically active at once. The retina receives multiple images simultaneously, some in focus and others blurred, and the brain must decide what to keep and what to suppress. With progressive glasses, we solve this mechanically by making deliberate eye movements to hit the correct zone. The optics stay still and the eye moves.

A contact lens removes that option entirely. The only usable variable left is the pupil itself. When we look up close, the pupil constricts. When we look far away, it enlarges. That is the one physiological change we can leverage. This is why many multifocal lenses place the near power in the center. When the pupil constricts for reading, a larger proportion of the light passes through the near zone. When the pupil dilates for distance, more of the outer rings contribute.

Even so, all zones are always optically active. Light still passes through every ring at once. The retina receives multiple images stacked perfectly on top of each other, some in focus, others blurred.

This is literally what comes to mind when I try to visualize a multifocal contact lens design. The central red dot represents the near prescription, the surrounding white ring the intermediate zone, and the outer red ring the distance zone.

At that point, the problem stops being optical and becomes neurological.

A useful analogy is driving in the rain. When you look down the road, the windshield wipers are still in your visual field. They move. They intermittently block parts of the scene. They are never actually in focus, unless you decide to stare at them, which is generally discouraged if you value your bumper. And yet, after a short time, you stop noticing them. The brain learns they are irrelevant and suppresses them, even though their physical effect never disappears. While the wipers are on, fewer photons from the road and the car ahead reach your eyes, simply because each pass of the blade briefly blocks part of the visual axis before moving on. So even though we don’t notice them, they are certainly having some detrimental effect on our quality of vision.

That adaptation to this is exactly what multifocal contact lenses rely on. Just as the brain learns to suppress the defocused wipers while preserving the sharp road ahead, it can learn to suppress defocused focal zones while preserving the zone that matters for the task at hand.

Where each multifocal contact lens differs is in how they present that defocus.

Most modern multifocal lenses use what I will call a “soft” optical design. This is my own terminology. In these designs, power transitions between rings are blended gradually, spreading defocus across many small zones. Optically, this is similar to having normal sized windshield wipers moving at the highest setting across your car window. Each pass blocks only a small amount at any given moment, but taken together they create a constant, low-level interference. The result is a smoother visual experience, but a weaker signal. Contrast is reduced everywhere, including where clarity matters most.

What I will call “harder” designs, again referring to the optical strategy rather than the lens material itself, take the opposite approach. Power is concentrated into fewer, more distinct zones. This more closely resembles a classic trifocal strategy, analogous to a single larger windshield wiper moving more slowly. The interruption is more noticeable, but it is also more predictable. Between passes, the view is cleaner. The brain is presented with stronger, more distinct signals and adapts by locking onto the one that matters.

In both cases, the brain is doing the same job: suppressing defocus. The difference is whether that defocus is spread thinly everywhere or confined to places the brain can more easily ignore.

Which design is better? There is no universal answer. People respond differently to different optical strategies, and multifocal lenses are no exception.

It is also difficult to make clean comparisons because the details of each design are not easy to access. Manufacturers tend to guard parameters such as zone size, curvature, and exact power distribution. Whether this is because they assume no one is interested or because the designs are genuine trade secrets is unclear. In practice, reverse engineering a multifocal lens well enough to know exactly how it is built is extremely challenging.

What I can say is that the multifocal lens I have had the most consistent success fitting recently appears to be built on a “harder” optical design chassis (One Day Ultra Multifocal, Bausch + Lomb). That observation is based on both the published literature and patient feedback. Anecdotally, over years of fitting a wide range of multifocal contact lenses, I do feel like patient satisfaction has tended to improve continuously in small, incremental steps with each new generation of multifocal contact lenses. With this particular lens, however, the improvement feels less incremental and more like a distinct step change in overall satisfaction. To understand why, it helps to compare multifocal contact lens designs to multifocal glasses. “Softer” contact lens designs parallel progressive glasses, while “harder” designs resemble trifocals. Paradoxically, the approach that is inferior in glasses appears, in my opinion, to translate into a superior solution in contact lenses.

My Thinking (Progressive vs. Trifocal)

Progressive lenses use a gradual change in power from top to bottom, making the transitions between zones essentially invisible. Trifocals, by contrast, use hard lines to clearly demarcate each zone (above).

In spectacle lenses, progressives dominate for good reason. They deliver continuous vision without visible lines. Trifocals, by contrast, are often treated as optical fossils. Three etched zones. Three powers. No subtlety.

We tend to dislike trifocal glasses for predictable reasons. Cosmetically, the lines advertise age whether you want them to or not. Functionally, crossing those lines produces image jump. Optically, there is no true in-between zone. You are either in one focal bucket or another.

When the same concept is translated into a contact lens, most of those drawbacks disappear. The frame is gone. The lens thickness is gone. The visible geometry is gone. What remains are the advantages.

There are no cosmetic lines. No image jump. Just clearly defined focal regions that deliver strong, unambiguous signals.

In that context, the features that made trifocals undesirable in glasses become strengths in a contact lens. “Harder” multifocal contact lens designs lean into this logic, while “softer” designs are more closely analogous to progressive glasses.

Visualizing the Difference

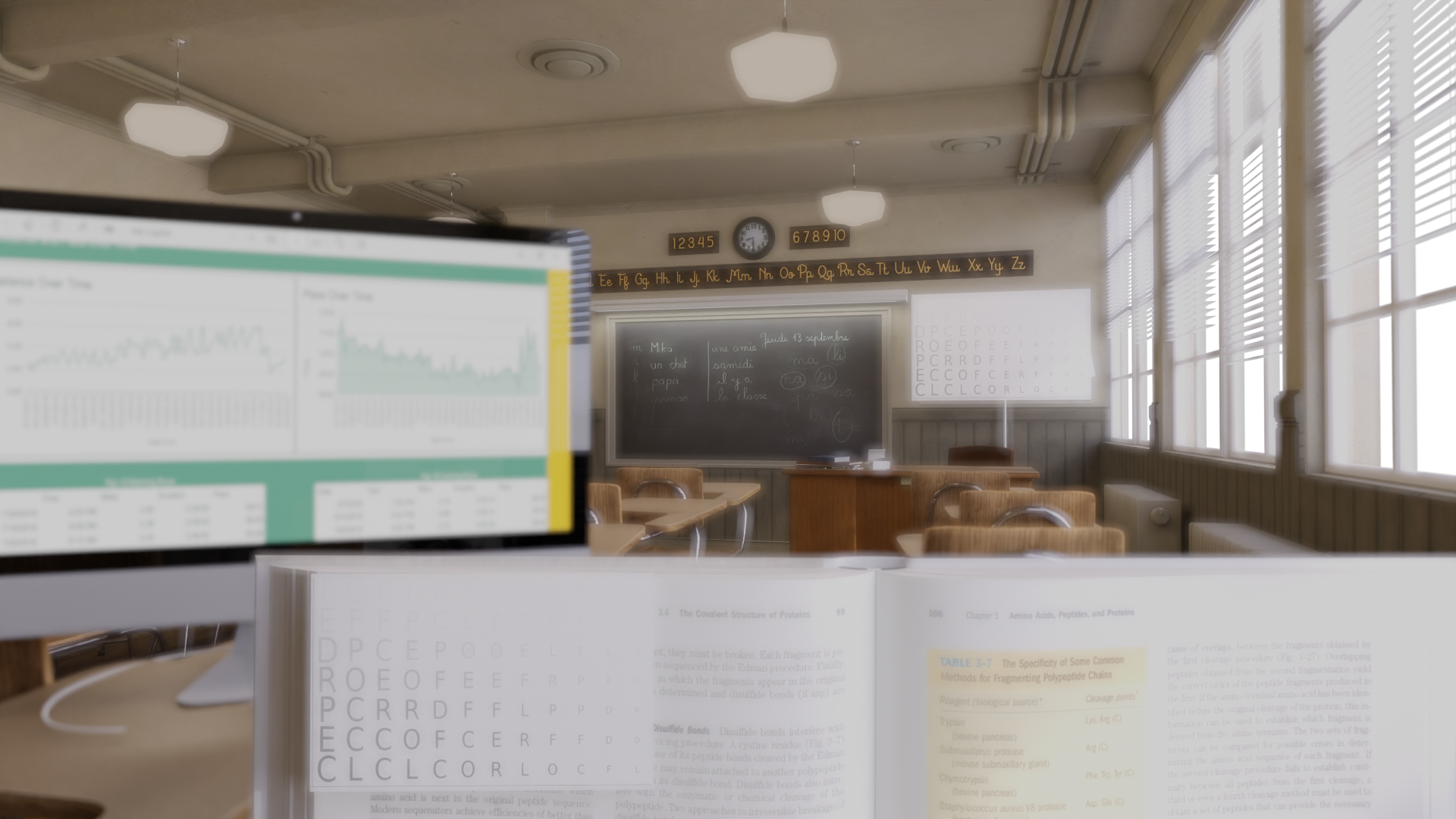

Rather than rely on intuition or sales diagrams, I built a simulation.

Using open-source 3D modeling software, Blender 5.0, I built a deliberately simple scene. A living room. A television across the room. A tablet held at reading distance. Nothing exotic, just the two visual demands that dominate modern life.

Rather than trying to simulate a multifocal lens directly, I approached the problem from first principles. What matters is not the lens itself, but the images it delivers to the brain.

I rendered the same scene multiple times, each time with the virtual camera focused at a different distance. One render was sharply focused on the television. Another was focused on the tablet. Additional renders covered intermediate focal depths. Each render represents what the retina would receive if that focal plane were dominant. I then composited these renders together, stacking them spatially so they perfectly overlapped, just as multifocal contact lens zones overlap on the retina. Crucially, they were not averaged. Each layer was given a weighted influence, simulating how much light from each focal zone would realistically contribute at a given pupil size. To approximate physiological behavior, I changed those weightings depending on the task. For near viewing, the near-focused layer was given greater influence to reflect pupillary constriction. For distance viewing, the balance shifted outward, increasing the contribution of distance-focused layers as the pupil expanded.

This approach mirrors how multifocal lenses actually work. The eye is never seeing one focal plane in isolation. It is always receiving a composite image made up of several focal planes at once, with relative dominance shifting rather than switching.

By doing the simulation this way, the differences between design philosophies become obvious. A “harder” design uses fewer focal layers (6.0m, 1.3m, 0.4m) with higher contrast between them. A “softer” design uses more layers (6.0m, 4.0m, 2.0m, 1.3m, 1.0m, 0.4m) with smaller differences between adjacent focal planes. The scene is the same. The task is the same. Only the structure of the composite changes.

What you see in the animation is not a theoretical lens diagram or an Instagram style blur filter. It is a close approximation of the visual input the brain is asked to interpret when wearing multifocal contact lenses.

This is the key point. This is the task being assigned. The brain must suppress, enhance, and resolve competing signals in real time. Some people adapt to this process more easily than others. If you spend a short time looking at the two animations below, you may start to notice this effect yourself. The videos can appear to become clearer over time as your brain begins to suppress certain information and amplify others, helping you extract what you need more efficiently.

Simulation: The “Harder” Design vs The “Softer” Design

You will want to view this on a computer monitor or tablet. A phone screen is simply too small to show the differences, especially since you likely have presbyopia (I mean why else would you read an article on multifocal contact lenses)

Click the slider above and drag it left and right. The animation on the left is the “harder” design, and uses three discrete focal planes: distance, intermediate, and near. Their relative influence changes based on pupil size, which shrinks for near tasks and expands for distance viewing.

What you should notice is not smoothness, but decisiveness. The television snaps into focus and you can see the score. The tablet snaps into focus and you can read the screen. As the camera transitions between tasks, there is a brief instability, but the targets themselves are clean and high contrast. The visual system is given a strong signal and left to do what it does best: choose.

The model on the right represents the “softer” design. It blends multiple focal depths, in this case six, into a continuous gradient. The transition feels calmer and more stable, with less perceptible flicker. Many of the larger elements in the scene appear reasonably clear.

But look more closely at the television and the tablet. Both are acceptable, but neither is excellent. The score on the TV is harder to read, and the tablet text looks slightly washed out.

At a glance, the two designs look similar. In practice, it is these small details, reading a score on a screen or a street sign at a distance, that tend to make or break the multifocal lens experience.

Why I Believe Hard Design Often Wins

Most people live at two visual extremes. Roughly fifteen inches for screens. Roughly twenty feet for everything else. Very little of daily life depends on perfect clarity at exactly four feet.

A harder multifocal design aligns with that reality. By prioritizing strong distance and near zones, it produces clarity where it actually matters. The trade-off is predictable. Sharper transitions increase the likelihood of halos and glare at night. Some patients tolerate that easily. Others do not.

This is not a flaw. It is an honest compromise.

The Takeaway

Multifocal optics is never about perfection. It is about tradeoffs, and deciding which limitations you are willing to accept.

At its core, the goal of any optical system is simple. Deliver as much accurate information about the target as possible to the retina, then let the original neural network, the brain, do what it does best. When the input data is clean and decisive, the brain has a much easier job refining and interpreting what it sees.

A design that tries to smooth everything risks leaving nothing truly sharp. A design that commits to specific focal goals gives the brain something concrete to work with. The success of this lens is not magic. It is a reminder that older optical ideas were not wrong. They were simply limited by the technology of their time.

Hide a trifocal inside a modern contact lens, and the logic suddenly makes sense again.

Dr. Robert Burke is an optometrist at Calgary Vision Centre. The thoughts, opinions, and analogies shared above are intended for education and entertainment purposes only (think of them like a friendly explainer, not a personal consultation.) Every set of eyes is different, and the right testing protocol depends on your specific vision needs, health history, and lifestyle. So if you're experiencing symptoms or just have questions about your vision, don’t rely on internet content alone, talk to your optometrist or health care provider directly. We’re here to help, but nothing beats an in-person exam with someone who knows your eyes.