Keep Your Eyes Up: Did Michelangelo go blind painting the Sistine Chapel?

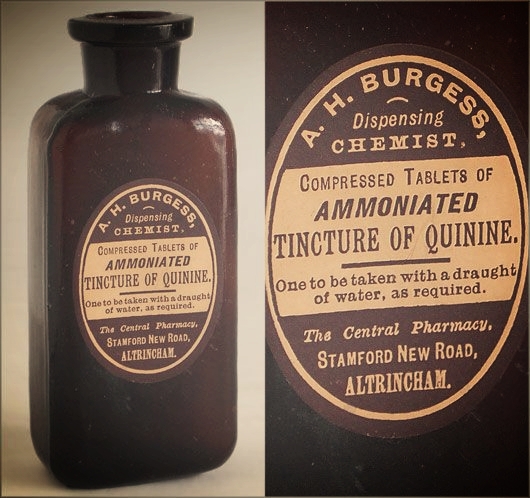

I get eyestrain just looking at this picture.

Imagine this: You’re 33. You’ve already carved your name into history with works like David and Pietà, and then Pope Julius II calls you personally (no big deal) and drops the ultimate commission on your lap: paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Now, most of us would be like, “Uh, can I get an ergonomic chair and some decent lighting first?” But not Michelangelo. He crawled, laid in awkward positions, craned his neck and in the process defied the laws of ergonomics—all while enduring what might be the most extreme case of eye strain in art history.

The Renaissance Daredevil

The Sistine Chapel’s Occupational Health and Safety department really dropped the ball on this one.

At 33, Michelangelo was already a bona fide superstar of the Renaissance. Sure, his sculpting prowess got all the glory, but his mind was a relentless factory of genius ideas too. When tasked with painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling in 1508, he wasn’t simply asked to flick some paint on a wall—he had to navigate the challenges of working in a vast, dim, and dusty cathedral, suspended on scaffolding, with his eyes locked onto a surface far above him for years on end.

Now, here’s the twist: historical accounts tell us that while he suffered seriously from temporary eye strain throughout this ordeal, he didn’t end up losing his sight. His eyes were taxed to the nth degree—like a smartphone battery running down after hours of nonstop gaming—but they didn’t give out permanently.

The Curious Case of Declining Focus

How the power of the human focusing system dwindles as we age aka why we need +2.50 drugstore reading glasses when we get older.

Let’s talk about how our eyes work. They have an impressive ability called "accommodation," which allows them to focus on objects at different distances. While presbyopia—the age-related decline in this ability—typically becomes noticeable in our 40s, the process actually starts much earlier, gradually unfolding from around age eight. In our younger years, we have such a surplus of focusing power that a slight annual decline hardly makes a dent; however, by our early 30s, these reserves can begin to wane noticeably. Even though we can still perform everyday tasks like reading small print, extended periods—say, 10 hours on a computer—will feel more taxing than they did in our 20s. In fact, studies suggest that our accommodative power can drop by up to 35% between ages 33 and 37. When you consider the relentless close-focus work Michelangelo was doing day in and day out at these ages, it’s easy to see how his visual system could have been pushed to its limits, resulting in temporary, intense fatigue without causing permanent damage. Would things have been different if he got the commission at 23 rather than 33? Perhaps the myth of a permanently blind, tortured artist took root because for centuries it seemed almost unfathomable that someone could spend years squinting in dim light at minute details without doing damage to their eyes—when nowadays gamers and office workers do just that every day without the catastrophic consequence blindness.

A Radical Theory: Nystagmus Under Extreme Strain

Interestingly, lying down on scaffolding and staring at a ceiling a few feet away might not have been the most taxing part of Michelangelo’s ordeal. Sure, that position—where you’re forcing your eyes to focus on something up close — certainly strained his vision. But here’s where it may get more extreme: he wasn’t just stuck in that one position. Michelangelo was constantly shifting between lying on his back while painting way up high and then climbing down the scaffolding and coordinating his work from ground level. When he managed things from below, he had to keep tilting his head upward, engaging a specific combination of eye alignment muscles that we hardly ever use for such prolonged, concentrated stretches. This combo of intense close-up focus and relentless upward gazing may have pushed his ocular system into overdrive, potentially triggering temporary, involuntary eye movements known as acquired nystagmus (minor eye tremors). It might sound wild, but given the sheer physical demands of his dual work positions, this theory about work-induced nystagmus holds some intriguing weight, although would still be a very rare diagnosis by modern standards.

Busting the Blindness Myth

The image of the tortured, blindingly-visioned genius is a compelling narrative—one that fits perfectly into our romanticized view of the suffering artist. But here’s the real deal: Michelangelo’s woes were all about extreme, temporary eye strain. After the Sistine Chapel ceiling was completed in 1512, his vision bounced right back. There’s no historical evidence that his eyes ever betrayed him permanently. In fact, he went on to produce more jaw-dropping masterpieces that shaped the course of art and architecture.

What's Next? The Renaissance Keep on Rolling

The Last Judgement, painted 25 years after the Sistine Chapel. Pretty good for someone who was apparently blind.

If you thought the Sistine Chapel was the end of the road, think again. Not only did Michelangelo recover from the ordeal, but he also embarked on other monumental projects:

The Last Judgment (1536–1541): Returning to the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo tackled an even more dramatic fresco that redefined emotional intensity in art.

Architectural Feats: His visionary designs for the Laurentian Library in Florence and the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome stand as testaments to his multifaceted genius.

Medici Chapels and Beyond: Michelangelo’s later sculptural and architectural endeavors proved that even after pushing his body—and his eyes—to the limit, he could still reinvent the face of art.

The Bottom Line

Michelangelo’s stint with eye strain during his colossal Sistine Chapel project wasn’t the tragic, permanent curse that later mythmakers would have you believe. It was a temporary occupational hazard—a testament to his willingness to push beyond normal human limits. His quick recovery and subsequent artistic achievements remind us that a little eye strain, even if it feels like you can’t possible stare at the computer screen for another minute, is hardly a death sentence for your vision.

Dr. Burke is an optometrist practicing at Calgary Vision Centre. Opinions above do not constitute medical advice, and readers should consult with their optometrist and health care team if they have questions or concerns about their eye health